Harvey Milk Terminal 1

Bell Aircraft coveralls, Evelyn DeLong Parris c. 1943–45

Hattie Snow Uniforms, Ogdensburg, NY

Courtesy of the National Park Service, Rosie the Riveter/WWII Home Front National Historical Park

RORI 706; L2024.0701.001

Propaganda and Women’s Wear

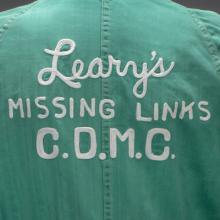

In 1942, the United States War Production Board, War Advertising Council, and Office of War Information coordinated a nationwide campaign to recruit women into the workforce. Propaganda recast traditional female roles and publicized women as vital to the success of an industrial nation at war. A barrage of posters, photographs, and advertisements featured women working in positions that were previously reserved for men. Content was designed to attract new workers and to convince men that female participation was temporary and necessary. Glamorized images reassured new recruits that their femininity would not be sacrificed by taking wartime work. Although women from all walks of life proved invaluable to the war effort, racial prejudice excluded women of color from government posters and only featured them in propaganda photographs.

Factory work modified women’s wear for industrial production. Blouses and dresses offered little protection and gave way to shirts, pants, and coveralls. Women tied long hair under a bandanna or other head covering. One Rosie recalled, “many of our mothers and aunts who worked in the defense plants never really adjusted to wearing what they considered to be men's clothing…whereas many of us younger women thought that pants and shirts were both very fashionable and chic.” The coveralls displayed here, worn by Evelyn DeLong Parris when she assembled Boeing B-29 Superfortress lower turrets at Bell Aircraft in Marietta, Georgia, were made specifically for factory work. Fashioned from durable, heavy cotton material, complete with stylish darts and pleats, the coveralls feature large pockets to hold tools and parts, and short sleeves to provide relief in warm weather.

[image]

It’s a Tradition with Us, Mister! 1943

J. Howard Miller (1918–2004) | Westinghouse Electric Corporation

Courtesy of Stanford University, Hoover Institution Library & Archives

R2024.0710.001

[clockwise from top right]

ID card, Barbara E. Pasco, sheet metal technician, Boeing Aircraft Company, Seattle c. 1943–45

RORI 2467; L2024.0701.092

ID badge, Priscilla L. Elder, electrician, Kaiser Richmond Shipyard No. 3 c. 1942–45

RORI 1173; L2024.0701.053

ID card, Barbara M. Nordstrom, riveter, Douglas Aircraft Co., Long Beach (El Monte), CA c. 1942–43

RORI 1055; L2024.0701.091

ID badge, Beatrice Keller, Kaiser Richmond Shipyard No. 2 c. 1942–45

RORI 735; L2024.0701.051

All objects are courtesy of the National Park Service, Rosie the Riveter/WWII Home Front National Historical Park.

Rosie the Riveter

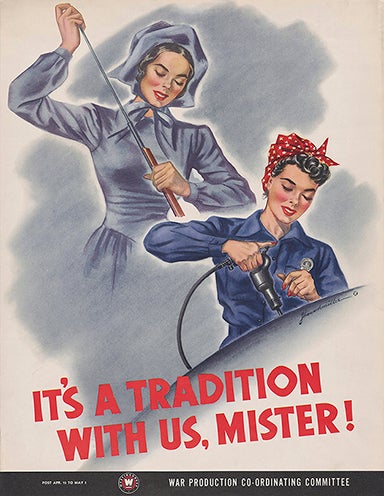

“Rosie the Riveter” was introduced to popular culture in a song by Redd Evans and John Jacob Loeb, performed by The Four Vagabonds and Allen Miller and his Orchestra in early 1943. Norman Rockwell’s Rosie the Riveter, featured on the May 29, 1943, cover of The Saturday Evening Post, reached millions of readers while the original painting toured the country in support of a War Bond drive. The image that is so widely associated with Rosie the Riveter today was illustrated by J. Howard Miller for Westinghouse Electric Manufacturing Company. Featuring a bandanna-clad woman flexing her right arm and proudly proclaiming, “We Can Do It!,” the poster was only displayed in Westinghouse factories for two weeks in February 1943. Miller’s “Rosie” did not achieve wider recognition until the 1980s, when the Washington Post published a poster from the National Archives collection and the Smithsonian Institution acquired the only other original example known in existence.

[image]

“Rosie the Riveter” 1942

Redd Evans (1912–72) & John Jacob Loeb (1910–70)

Paramount Music Corporation, New York

Courtesy of the National Park Service, Rosie the Riveter/WWII Home Front National Historical Park

RORI 1175; L2024.0701.007

[image]

“We Can Do It!” 1943

J. Howard Miller (1918–2004) | Westinghouse Electric Corporation

Courtesy of the Smithsonian Institution, National Museum of American History

R2024.0707.001

Welding hood c. 1942–45

The Huntsman Shield, Salt Lake City

Courtesy of the National Park Service, Rosie the Riveter/WWII Home Front National Historical Park

RORI 2935; L2024.0701.050

The Kaiser Shipyards in Richmond

The Kaiser Shipyards in Richmond comprised the world’s largest shipbuilding facility during the Second World War. Founded in 1941 to construct British merchant ships, the shipyards refocused on production for the U.S. Maritime Commission after war was declared. Kaiser pioneered prefabricated techniques that utilized welding rather than traditional riveting, allowing ships to be constructed in a few weeks rather than over months. Teams welded hulls together in concrete-lined drydocks while specialized shops built prefabricated sections that were lowered into place. The Richmond shipyards made national headlines in 1942 when the Liberty Ship SS Robert E. Peary was constructed in four-and-a-half days. Surpassing the motto “ten down the ways in thirty-one days,” one vessel on average was built every day by the Fall of 1943—with a staggering 747 ships completed when operations ceased in 1945.

The Kaiser Shipyards began hiring women in 1942; two years later, approximately 24,500 female workers constituted twenty-seven percent of its labor force. Although they received the same pay as their male counterparts, women in the Richmond shipyards were excluded from union voting and higher-level promotions. Bernice Grimes, a scaler who prepped welded surfaces at Shipyard 1, stated of her male coworkers, “I don’t really remember them giving me a bad time, but you couldn’t get any information out of them.” Kay Morrison, who joined Kaiser as a tack welder in Shipyard 2, attributed her promotion to certified journeyman welder to training by a benevolent male supervisor. Women also worked as burners, cutting steel plate with acetylene torches, as shipfitters and flangers, aligning large sections before they were permanently joined, and in other trades and non-skilled positions. The welding hood pictured above, inscribed “Baby Face,” “Sweet Stuff,” and “Call Me Sugar,” suggests the harassment encountered by some women in the fourteen shipyards located throughout the San Francisco Bay Area during the Second World War.

[image]

Runner up in Yard 3 “Joan of Arc” contest July 27, 1943

Kaiser Shipyard No. 3, Richmond, CA

Courtesy of the Richmond Museum of History and Culture

R2024.0703.012

[left to right]

Fiberglass hardhat, Precious Mack, Kaiser Richmond Shipyard Warehouse c. 1943–45

Courtesy of the Richmond Museum of History and Culture

RMA 2000.030.1; L2024.0703.009

Aluminum hardhat, Rena Pearl Jung Chung, Kaiser Richmond Shipyard No. 1 1942–45

Courtesy of the Richmond Museum of History and Culture

RMA 2909-32; L2024.0703.001

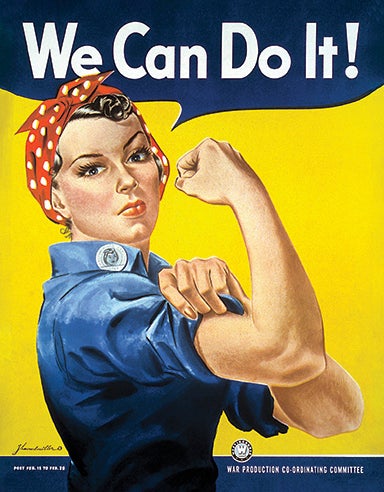

Diversity and Discrimination in Bay Area Industry

With the need for wartime-emergency labor, women from minority groups joined the industrial workforce in record numbers. Thousands of Latin American women traded more traditional work for higher wages in manufacturing and shipbuilding. Native American women, some with families who had migrated to work at the Santa Fe Railroad terminus in Richmond, California, took wartime jobs at the new shipyards. Hundreds of Chinese American women worked in the San Francisco Bay Area defense industry in 1943, the same year that the Chinese Exclusion Act and other racist policies aimed at Asian immigrants started to roll back. However, the vast majority of women of Japanese descent were excluded from war work when they and their families and friends were forcefully removed from their homes and ordered to live in incarceration camps.

The Black population of Richmond grew from 270 in 1940 to approximately 10,000 by 1945. Precious Mack, who wore the Kaiser Richmond Shipyard Warehouse hardhat displayed here, moved from Shreveport, Louisiana, with her family and lived in a trailer until they found a wartime apartment. Shipbuilding labor unions denied membership to Black applicants at first, making jobs unattainable in shipyards. Under pressure from civil rights organizations and the Fair Employment Practices Committee, unions issued individual clearances before creating segregated branches without equal rights. Faith McAllister, a Black shipyard worker from Louisiana, stated that, “discrimination was hard, but we’ve been doing it for years and years. At least we got paid for putting up with it out here.”

[images]

We Also Serve: 10 percent of a Nation Working and Fighting for Victory 1944

Ben Watkins and Charles F. Tilghman | Tilghman Press, Berkeley, CA

Courtesy of San Francisco State University, Labor Archives and Research Center

L2024.0702.003, R2024.0702.003

Continental Airlines coveralls, Sue Gaiser Graham c. 1942–45

Johnson & Co., St. Peter, MN

Courtesy of the National Park Service, Rosie the Riveter/WWII Home Front National Historical Park

RORI 4214; L2024.0701.095

Aircraft Production

Industrial production during the Second World War accelerated on a scale not seen previously or since. Auto factories converted to aircraft manufacturing or switched to making tanks, trucks, and jeeps. Companies that made refrigerators, radios, and myriad other domestic goods quickly retooled for war. Years of experience are normally required to learn the skills needed to manufacture complex equipment. To streamline production, factories restructured manufacturing processes and divided traditional trades into highly specialized work. Rather than moving from one project to the next, entry level workers started with repetitive tasks that were often physically demanding.

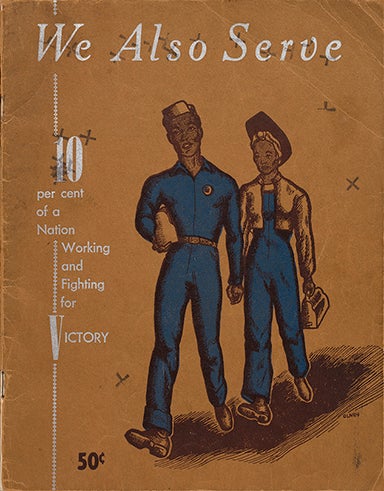

Women comprised sixty-five percent of America’s aviation-related workforce at the height of wartime production. Rarely afforded fair and equal pay, women performed all varieties of aircraft work, from operating sheet metal presses and assembling engines to wiring electrical panels and plumbing hydraulic systems. Riveters and buckers fastened prefabricated aluminum aircraft components into larger structures. Working as a team, the riveter used an air hammer to drive a rivet from the outside of a structure against a bucking bar held by a bucker on the inside. Sue Gaiser Graham wore the coveralls displayed here as part of the only all-female crew at the Continental Airlines maintenance facility at Lowry Air Force Base in Denver. Her crew, who performed field modifications on Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress and North American P-51 Mustang aircraft, proudly embroidered “Leary’s Missing Links”—a nickname derived from their male supervisor’s last name—on the back of their coveralls.

[image]

Susan Esposito (left) and her cousin Rose Hickey after setting a record for assembling a TBM Avenger wing trailing edge in four hours, ten minutes 1943

General Motors Eastern Aircraft Division, Trenton, NJ

Courtesy of the National Park Service, Rosie the Riveter/WWII Home Front National Historical Park

R2024.0701.0119

Northwest Airlines coveralls, Lois Amy Johnson Schmidt 1943–45

The Hinson Manufacturing Co., Waterloo, IA

Courtesy of the National Park Service, Rosie the Riveter/WWII Home Front National Historical Park

RORI 3335; L2024.0701.076

Perseverance and Recognition

Women assisted with drafting, engineering, testing, and training in addition to industrial production work. They worked as mechanics, repairing and maintaining vehicles, and as conductors and drivers. Women Ordnance Workers occupied the most dangerous jobs, making ammunition and explosives. Women worked in agriculture and food service, producing rations for troops and provisions for the home front, and as clerks, typists, and other traditionally “pink collar” jobs in the defense industry. Though equality was rare in the wartime workforce, women persevered in the face of adversity. Helen Studer, a riveter at Douglas Aircraft, recalled, “the men really resented the women very much, and in the beginning, it was a little bit rough. You had to hold your head high and bat your eyes at ‘em. You learned to swear like they did…after a while, they realized it was essential that the women worked there.”

Seventy-five percent of 13,000 women polled in 1944 planned to continue working, and the majority preferred to stay in their respective industries. As the war ended, massive layoffs displaced millions from positions that either disappeared or were returned to former servicemen. Mae Krier, a riveter at Boeing Aircraft Company in Seattle, recalled that, “men came home to fancy parades but women in the factories got pink slips.” Few women remained in wartime-related industries, although some aircraft companies offered postwar career paths. Many former full-time homemakers refocused on domestic duties. Countless other women who needed to work returned to gender-stratified positions. Yet women also found jobs in peacetime manufacturing and attended colleges and trade schools using their wartime savings—initiating changes to the American workforce that continue today.

Largely forgotten for decades, woman defense workers began to receive public recognition in the 1990s as Americans commemorated the fiftieth anniversary of the Second World War. Many who never considered themselves as “Rosies” became aware of their importance. After years of lobbying by former defense workers Phyllis Gould and Mae Krier, on April 10, 2024, Krier and twenty-six other surviving Rosie the Riveters accepted the Congressional Gold Medal, the nation’s highest civilian honor, on behalf of more than sixteen million others. Lila Tomek, who assembled aircraft at the Glenn L. Martin plant near Omaha, attended the ceremony and remarked, “we didn’t get any special thanks when the war ended. So it was such a surprise to be acknowledged all those years later. I had to pinch myself to really believe it.”

[image]

Bronze replicas of Rosie the Riveter Congressional Gold Medal 2024

United States Mint, Washington, D.C.

Courtesy of the National Park Service, Rosie the Riveter/WWII Home Front National Historical Park

L2024.0701.128.01–.02, L2024.0701.129.01–.02