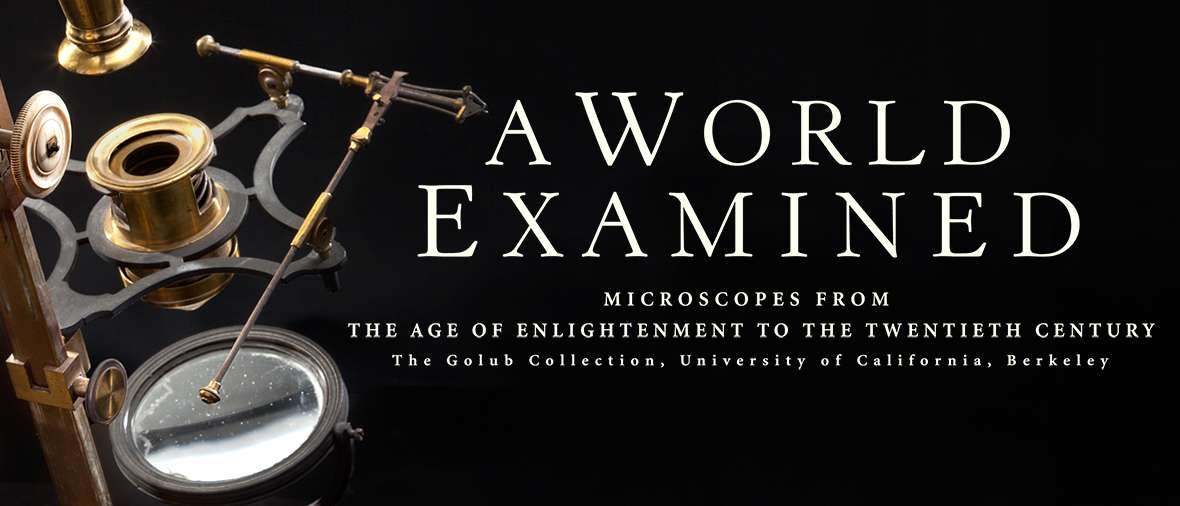

A World Examined: Microscopes from the Age of Enlightenment to the Twentieth Century

—Robert Hooke (1635–1703),

in preface to Micrographia: or some Physiological Descriptions

of Minute Bodies Made by Magnifying Glasses, 1665

A World Examined: Microscopes from the Age of Enlightenment to the Twentieth Century

The microscope is a relatively young invention. Although magnifiers and "burning glasses" are referenced in ancient Chinese texts and in the first-century CE writings of Roman philosophers, the use of an optical instrument for observing microscopic specimens dates only to the sixteenth century when European scientists first used lenses to magnify objects. Around 1590, Dutch spectacle maker Hans Janssen placed two magnifying lenses in series to gain greater magnification. Englishman Robert Hooke, one of the most important scientists of his age, used this compound microscope in the mid-seventeenth century and documented his observations in the first scientific bestseller, Micrographia: or some Physiological Descriptions of Minute Bodies Made by Magnifying Glasses (1665). Hooke's vivid descriptions and extraordinary copper-plate illustrations of dozens of minuscule phenomena—animal, vegetable, mineral, even man-made objects such as the point of a needle or a razor's edge—were a public sensation, and his work stands as a remarkable testament to the keen and curious minds operating at the dawn of the Age of Enlightenment. The invention of the microscope and its rapid evolution were perfectly timed for those eager to employ the powers of reason to learn more about their world.

Dutchman Antonie van Leeuwenhoek, a textile merchant by day but an expert lens grinder after hours, was one of the legions of scientists inspired by Hooke's publication. Leeuwenhoek achieved extraordinary results from his simple device made from a single polished glass bead held between two plates. Leeuwenhoek was able to clearly view specimens magnified to 247 times their actual size, and his reports to the Royal Society of London encouraged countless others to join the burgeoning community of microscopists at the end of the seventeenth century.

In the eighteenth century, the microscope became a favorite diversion among the upper classes throughout Europe—an ubiquitous feature in the parlor of esteemed households. Solar and lucernal microscopes, which projected magnified images onto a screen, were used in private homes for study and education, as well as for entertainment. The instrument's surge in popularity spurred innovations and improvements. A tremendous variety of microscope designs were introduced in quick succession, particularly by English makers: Edmund Culpeper's concave sub-stage mirror to enhance illumination of specimens (c. 1730); John Cuff's improved focusing mechanism and stage design for easier access to the specimen (1744); and George Adams, Sr.'s rotating disc of objective lenses (1746).

During the late nineteenth century, German microscope makers advanced the design of optical instruments to make the microscope a practical and modern research tool. Ernst Leitz's revolving turret (1863) allowed the quick and easy change of objective lenses while viewing a particular specimen. Carl Zeiss's collaboration with physicist Ernst Abbe revolutionized the microscope with high-quality lenses, large apertures, and the practical use of immersion oil, resulting in devices that, by the end of the 1880s, achieved the highest theoretical limit of resolution with little or no optical distortion.

From the mid-seventeenth-century simple microscopes like those of Antonie van Leeuwenhoek, to the modern compound optical devices by German makers during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, these are the instruments that revealed the long-held secrets of the natural world—the existence of microorganisms, the structure of biological cells, and the composition and operation of a variety of previously unseen life forms. Nearly 350 years after Robert Hooke introduced a "new visible world,” we continue to rely on the microscope in our eternal quest to better understand the world we inhabit and the challenges posed by that which remains invisible to the unaided eye.

This exhibition was guest curated by Steven Ruzin, Ph.D., Director of the CNR Biological Imaging Facility and Curator of The Golub Collection at the University of California, Berkeley.

"England's Leonardo"

Robert Hooke can arguably be called "England's Leonardo" in reference to the supremely multi-talented artist of the Italian Renaissance—Leonardo da Vinci. Hooke's areas of expertise included architecture, astronomy, biology, chemistry, geology, physics, and mathematics. As Curator of Experiments at the Royal Society of London, Hooke documented his microscopic observations in the 1665 publication, Micrographia: or some Physiological Descriptions of Minute Bodies Made by Magnifying Glasses. His vivid descriptions of objects ranging from ice crystals to a fly's eye were accompanied by Hooke's highly detailed and beautifully rendered copperplate engravings, some of which fold out to four times the size of the book. Hooke famously coined the biological use of the word "cell" while describing the structure of cork, which reminded him of a monk's quarters. His delight in discovering the "highest perfection" in all natural forms is evident in his wonderment at the mechanics of the lowly flea and "the beauty of it...all over adorn'd with a curiously polish'd suit of sable Armour, neatly jointed, and beset with multitudes of sharp pins, shap'd almost like Porcupine's Quills." Hooke's observations and illustrations inspired a multitude of other scientists at the dawn of the Age of Enlightenment to examine and reveal the secrets of a previously unseen microscopic world.

Micrographia: or some Physiological Descriptions of Minute Bodies Made by Magnifying Glasses 1665

Robert Hooke (1635–1703), London

Schem. XXXIV (flea)

The Golub Collection,

University of California, Berkeley

L2011.2301.065

©2011 by the San Francisco Airport Commission. All rights reserved