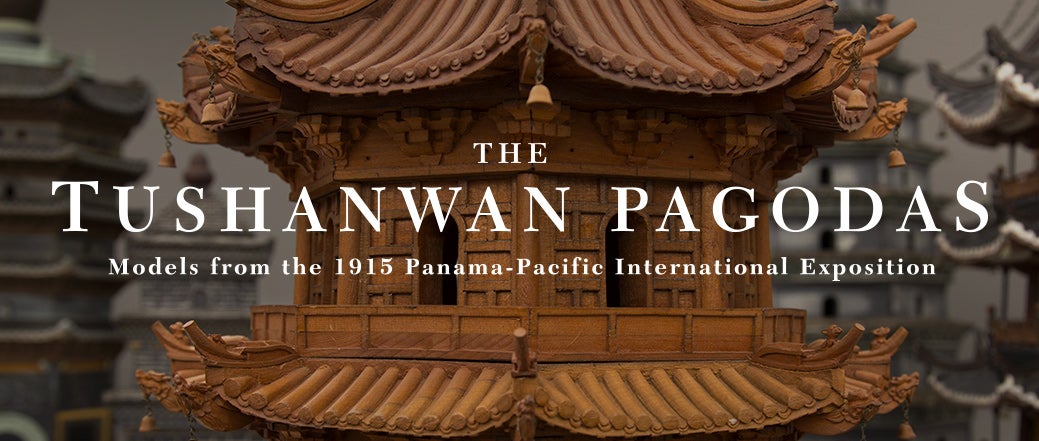

The Tushanwan Pagodas: Models from the 1915 Panama-Pacific International Exposition

The Tushanwan Pagodas: Models from the 1915 Panama-Pacific International Exposition

A century ago, San Francisco hosted a world’s fair that drew more than eighteen million visitors to a 635-acre wonderland of exhibits constructed along the city’s northern bay shore. The Panama-Pacific International Exposition, officially a celebration of the recently completed Panama Canal, was a characteristically audacious demonstration of the city’s remarkable recovery from the devastating earthquake and fire of 1906. Domed palaces housing international exhibitions of art, culture, and industry represented a microcosm of the world at large.

The Chinese Republic, barely three years old, was a key participant in the fair with a two-and-a-half acre pavilion that included a pagoda, an elaborately carved gateway, two teahouses, and a replica of Beijing’s Hall of Supreme Harmony. China was also well represented in the Palace of Education, which featured an exhibition of remarkable craftsmanship by teenage boys and young men working at Shanghai’s Tushanwan workshops—eighty-four hand-carved models of extant pagodas located throughout China. Tushanwan, which translates to “Earthen Hill Bay,” refers to an area of Xujiahui (called Zikawei or Siccawei by Westerners), the historically Catholic district that was on the outskirts of Shanghai one hundred years ago. Xujiahui translates as “meeting place of two rivers on the Xu family property.” Xu refers to the surname of an early and important Chinese Catholic convert, the Ming Dynasty scholar-official Xu Guangqi (1562–1633) and his Catholic descendants. By the nineteenth century, the Catholic community at Xujiahui included an observatory, a natural history museum, and several schools and orphanages. The Tushanwan woodshop, led by Bavarian-born Brother Aloysius Beck (1854¬¬–1931), was part of a Jesuit-run vocational arts and crafts training school for orphaned boys who exhibited particular artistic talent.

Brother Beck wished to produce a comprehensive study of the Chinese pagoda—the multi-tiered structure with upturned eaves that had long fascinated the West. The presentation of the models in San Francisco was intended to demonstrate the quality of training the Jesuits were providing at Tushanwan. Hand-carved from blocks of teak and other woods, and sometimes elaborately painted, the models present the extraordinary aesthetic, material, and scalar variety of China’s most familiar building typology. Some models are accurate reproductions of pagodas at their intended 1:50 scale, while others are more imaginatively rendered. Discrepancies in details and in scale reflect the limitations of Brother Beck’s reliance on an extensive network of fellow missionaries located throughout China. Interestingly, while many models depict pagodas in their pristine state, others are meticulously rendered with all their signs of age and neglect—missing roof panels, broken cornices, and some with overgrown vegetation.

Conceived to be sold as a single collection for systematic study at a museum or a university, the sheer size and quantity of the models made this goal difficult. Ultimately, they were purchased by The Field Museum of Chicago and shipped to their storage vaults at the close of the fair in 1915. Rarely shown, and never exhibited as a set, they remained largely out of sight until their deaccession by the museum and purchase in 2007 by a private party who desired to share them with the public. Now, for the first time since their original presentation at the Panama-Pacific International Exposition in 1915, the Tushanwan pagodas are exhibited together for visitors to the city in which they debuted. Brother Beck’s wooden models stand as intrinsically compelling examples of fine craftsmanship, while reminding us of a remarkable episode of transcultural exchange that occurred one hundred years ago.

[inset top image]

Interior of the Tushanwan carpentry workshop, with Brother Aloysius Beck at the center in the foreground c. 1920s;

Shanghai, China; California Jesuit Archives, Santa Clara University;

R2014.2608.003

[inset bottom image]

Brother Aloysius Beck and three orphans posing with their handiwork at the Tushanwan Catholic orphanage and woodshop c. 1929;

Shanghai, China; California Jesuit Archives, Santa Clara University;

R2014.2608.001

All objects are presented courtesy of the Jeffries Family Private Collection. SFO Museum is grateful to Mee-Seen Loong and William Ma for their generous assistance with this exhibition; and to Brother Daniel Peterson, Province Archivist at Santa Clara University; Susan Goldstein, City Archivist at the San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library; Patricia L. Keats, Director of the Library and Archives at the Society of California Pioneers, and Clay-Edward Dixon, Head of Collection Development at the Flora Lamson Hewlett Library of the Graduate Theological Union. Special thanks to Tom DeCaigny, Director of Cultural Affairs, San Francisco Arts Commission, and Jill Manton, Director of Public Art Trust and Special Initiatives, San Francisco Arts Commission, for introducing this collection to SFO Museum.

100 Years: Panama-Pacific International Exposition

This exhibition is part of the citywide centennial celebration of the Panama-Pacific International Exposition. For more information on related events and programming scheduled by San Francisco’s cultural, civic, and historical organizations throughout the year, please visit www.ppie100.org.

©2015 by the San Francisco Airport Commission. All rights reserved.