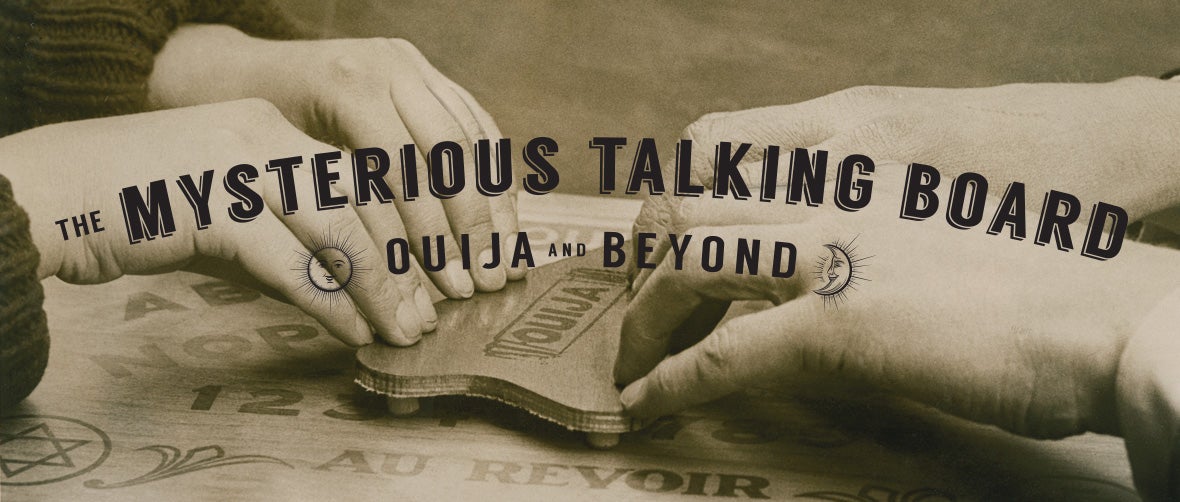

The Mysterious Talking Board: Ouija and Beyond

The Mysterious Talking Board: Ouija and Beyond

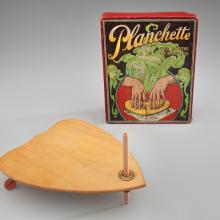

Talking boards have their roots in Spiritualism, a belief in the ability of the dead to communicate with the living. Spiritualism began to spread in the United States after the Fox sisters, aged eleven and fourteen, claimed to have communed with a spirit through mysterious raps they heard in their Hydesville, New York, home in 1848. Over the ensuing decades, a number of interesting methods were devised to communicate with spirits. In 1886, the press reported on a device used by some Spiritualists in Ohio—a talking board with letters, numbers, and a planchette-like device that pointed to the letters. Spirits could spell out their communications with the living, while the living simply held their hands on the planchette as it moved towards various letters.

Talking boards have their roots in Spiritualism, a belief in the ability of the dead to communicate with the living. Spiritualism began to spread in the United States after the Fox sisters, aged eleven and fourteen, claimed to have communed with a spirit through mysterious raps they heard in their Hydesville, New York, home in 1848. Over the ensuing decades, a number of interesting methods were devised to communicate with spirits. In 1886, the press reported on a device used by some Spiritualists in Ohio—a talking board with letters, numbers, and a planchette-like device that pointed to the letters. Spirits could spell out their communications with the living, while the living simply held their hands on the planchette as it moved towards various letters.

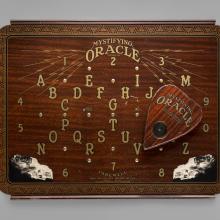

In 1890, Charles Kennard of Baltimore, Maryland, formed the Kennard Novelty Company with the help of several other investors, including Elijah Bond and William Fuld, to exclusively produce talking boards using the name Ouija board. Allegedly, they sought guidance from the board in naming it, and it replied “Ouija,” which the board explained, meant good luck. As the story goes, in 1891, Bond, accompanied by his sister-in-law Helen Peters, an acclaimed medium, brought the device to the patent office in Washington, D.C. The chief patent officer required him to prove that it worked by spelling out his name—supposedly unknown to Bond and Peters—in order to grant the patent. The two communed with the spirit realm, and to the shock of the patent officer, the Ouija board successfully spelled out his name. The wildly successful Ouija board was then marketed as both an oracle device and amusing parlor game.

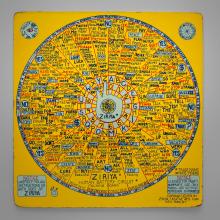

Shortly after, the business was reorganized and became the Ouija Novelty Company, largely run by William Fuld. Fuld’s brother Isaac joined him in 1897. But for various reasons, Isaac was expelled from the company in 1901, creating a family feud that would continue for decades. William then reestablished his business as the William Fuld Manufacturing Company. Isaac went on to create his own talking board, nearly identical to his brother’s, which he named the Oriole board. Dozens of others offered interesting versions of talking boards over the decades using a variety of names, although none surpassed William Fuld’s Ouija board in popularity. Many of these knockoffs featured an array of colorful imagery, from Egyptian sphinxes to swamis, fortune-tellers, and witches.

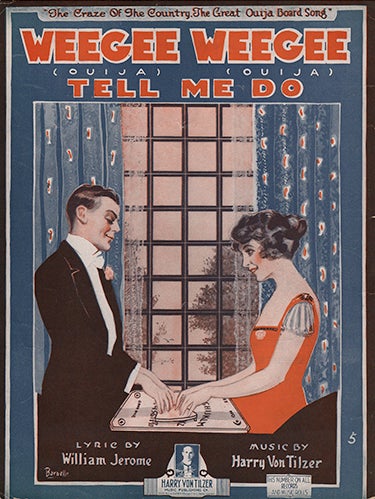

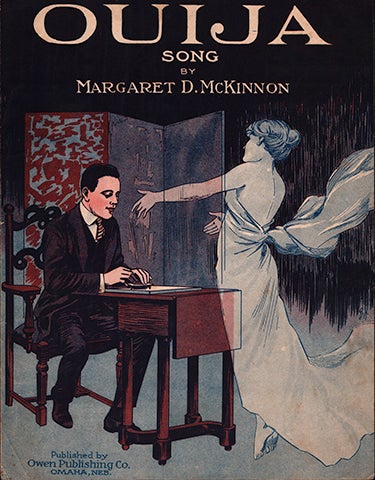

The public turned to talking boards for a variety of reasons. Some claimed that spirits dictated entire books to them via the Ouija board, such as Jap Herron (1917), purportedly penned by a posthumous Mark Twain through the medium of Emily Grant Hutchings. World Wars I and II caused a surge in sales of talking boards as many civilians hoped to get in touch with loved ones who had lost their lives during the wars. Others turned to talking boards to seek advice about their love lives or for guidance during troubled times. The Ouija board permeated popular culture—a Norman Rockwell painting of a man and woman using a Ouija board appeared on the cover of a 1920 Saturday Evening Post. Even sheet music incorporated the Ouija board, such as “Weegee, Weegee, Tell Me Do” (1920).

The public turned to talking boards for a variety of reasons. Some claimed that spirits dictated entire books to them via the Ouija board, such as Jap Herron (1917), purportedly penned by a posthumous Mark Twain through the medium of Emily Grant Hutchings. World Wars I and II caused a surge in sales of talking boards as many civilians hoped to get in touch with loved ones who had lost their lives during the wars. Others turned to talking boards to seek advice about their love lives or for guidance during troubled times. The Ouija board permeated popular culture—a Norman Rockwell painting of a man and woman using a Ouija board appeared on the cover of a 1920 Saturday Evening Post. Even sheet music incorporated the Ouija board, such as “Weegee, Weegee, Tell Me Do” (1920).

Long after William Fuld began making Ouija boards commercially in the 1890s, talking boards remained a favored pastime. Parker Brothers purchased the rights to the Ouija board from the Fuld family in 1967. Ouija board sales soon surpassed those of Monopoly. For more than one hundred and twenty-five years, the talking board has intrigued the public. This exhibition traces the device’s history and features boards from the 1890s to the present.

This exhibition was made possible by generous loans from Eugene Orlando of the Museum of Talking Boards and Robert Murch of the Talking Board Historical Society. Special thanks to Eugene Orlando and Robert Murch for contributing their extensive research on the history of talking boards.

© 2016 by San Francisco Airport Commission. All rights reserved.