Inspired Design: Shaker Furniture from the Benjamin Rose Collection

Inspired Design: Shaker Furniture from the Benjamin Rose Collection

Shaker Design

Shaker Design

The most successful of all American communal sects, the Shakers first established societies in New York and New England in the last two decades of the 1700s. Members strove to create a divine society – heaven on earth. Every task they undertook whether large or small was conducted with piety, as the community's founder, Mother Ann Lee once instructed: “Put your hands to work and your hearts to God.” The Shakers valued honesty, simplicity, utility, and fine craftsmanship. These qualities were thoughtfully embodied in the furniture and handicrafts they produced. From storage chests to oval boxes and baskets, each individual item was constructed with care.

As with their architecture, Shaker furniture eliminated unnecessary ornament, instead, emphasizing clean lines and purity of form. This distinctive Shaker style stems from eighteenth-century American vernacular furniture. Shaker craftsmen imitated conventional forms such as the ladder-back chair and blanket chest, adapting pieces to suit their own aesthetic. From the 1820s to the 1860s, known as the classic period in Shaker design, self-sufficient Shaker communities produced all of their own furnishings. Tables, beds, desks, benches, clocks, and stools were some of the many functional yet refined items they fabricated. Artisans also meticulously crafted built-in wall storage units with drawers and cupboards.

eighteenth-century American vernacular furniture. Shaker craftsmen imitated conventional forms such as the ladder-back chair and blanket chest, adapting pieces to suit their own aesthetic. From the 1820s to the 1860s, known as the classic period in Shaker design, self-sufficient Shaker communities produced all of their own furnishings. Tables, beds, desks, benches, clocks, and stools were some of the many functional yet refined items they fabricated. Artisans also meticulously crafted built-in wall storage units with drawers and cupboards.

The Shakers made furniture with locally available woods, including maple, cherry, and pine, which they often lightly stained or painted. Many of the pieces feature remarkable joinery. Shaker craftsmen gained a reputation for their outstanding workmanship and sold furniture, baskets, boxes, and other domestic items to the outside World as a means of supporting their communities. The village established at Mount Lebanon, New York, was particularly renowned for the chairs they manufactured for sale. The Shakers also pioneered the industry of selling seeds in packets and retailed a variety of herbal medicines and

agricultural products.

The Shakers viewed progress as a gift and embraced new technologies such as electricity and steam power, which enabled daily labors to be completed more quickly and efficiently. When they became available, craftsmen used circular saws, lathes, and mortising machines, without compromising the quality of their furniture. The Shakers were also innovators and invented a number of new technologies such as a prototype washing machine; the flat broom; waterproof, wrinkle-resistant clothing; and metal

The Shakers viewed progress as a gift and embraced new technologies such as electricity and steam power, which enabled daily labors to be completed more quickly and efficiently. When they became available, craftsmen used circular saws, lathes, and mortising machines, without compromising the quality of their furniture. The Shakers were also innovators and invented a number of new technologies such as a prototype washing machine; the flat broom; waterproof, wrinkle-resistant clothing; and metal

pen nibs.

Although Shaker membership and the sale of Shaker goods declined after the Civil War, several communities persevered in smaller numbers. In the 1920s, many museums and private collectors began to take an interest in American folk art and discovered the austere beauty of Shaker furnishings. Shaker forms also influenced modern American and Scandinavian design of the 1950s and 1960s. Inspired Design: Shaker Furniture from the Benjamin Rose Collection features a variety of Shaker furnishings from the communities of  Mount Lebanon and Watervliet, New York; Canterbury and Enfield, New Hampshire; Hancock and Harvard, Massachusetts; Enfield, Connecticut; Sabbathday Lake, Maine; and Union Village, Ohio.

Mount Lebanon and Watervliet, New York; Canterbury and Enfield, New Hampshire; Hancock and Harvard, Massachusetts; Enfield, Connecticut; Sabbathday Lake, Maine; and Union Village, Ohio.

Following Mother Ann Lee's death, Father James Whittaker (1751–87), who was followed by Father Joseph Meacham (1742–96) and Lucy Wright (1760–1821), helped lead the Shakers in the following decades. A set of Millennial Laws was drafted in 1821 that guided communities in all aspects of life from orderly worship practices and regulated dance to uniform architectural design. The Shakers relinquished the right to hold personal property of any kind, marry, or bear children. Men and women lived together as brothers and sisters, committed to a life of celibacy, and held all material possessions in common.

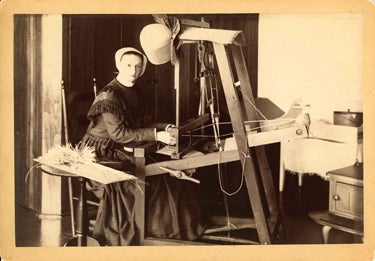

By 1840, an estimated five thousand or more Shakers lived in nineteen principal communities in New England, New York, Ohio, and Kentucky. Brothers and sisters lived in dormitory accommodations in dwelling houses separated by sex. Males and females used separate stairways, and meeting houses had separate entrances and seating arrangements. Daily labors were also divided by gender. Shaker communities were agriculturally-based. Communities grew their own produce, raised livestock, wove cloth, made finely-crafted furniture, and sold a variety of goods to what they referred to as the [outside] “World.”

By 1840, an estimated five thousand or more Shakers lived in nineteen principal communities in New England, New York, Ohio, and Kentucky. Brothers and sisters lived in dormitory accommodations in dwelling houses separated by sex. Males and females used separate stairways, and meeting houses had separate entrances and seating arrangements. Daily labors were also divided by gender. Shaker communities were agriculturally-based. Communities grew their own produce, raised livestock, wove cloth, made finely-crafted furniture, and sold a variety of goods to what they referred to as the [outside] “World.”

This type of communal living may have appealed to many for both spiritual and practical reasons. Membership freed individuals from the responsibility of individual land ownership, while providing converts with clothing, daily meals, and jobs. It also liberated many from the constraints of marriage and childbirth.  Although the Shakers chose not to procreate, families with children often joined, and communities also adopted children. At the age of twenty-one, these young adults could either choose to become full covenant members or leave to live in the World.

Although the Shakers chose not to procreate, families with children often joined, and communities also adopted children. At the age of twenty-one, these young adults could either choose to become full covenant members or leave to live in the World.

As the Industrial Revolution and urbanization progressed at a rapid pace during the last few decades of the 1800s, Shaker membership began to dwindle. By 1947, only three Shaker villages remained. Although they faced great changes, these communities persevered, two of them well into the late 1900s. A small group continues to practice the Shaker religion in Sabbathday Lake, Maine. Today, the Shakers are most remembered as an enduring communal sect who produced some of the finest nineteenth-century American domestic furniture.

Who Were the Shakers?

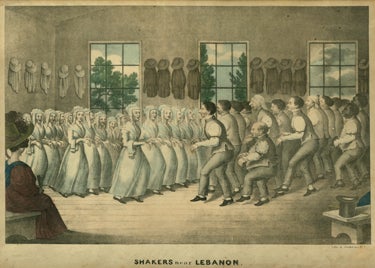

Mother Ann Lee (1736–84) left Manchester, England, for New York in 1774 with eight followers, in order to establish a new Christian religious sect. The United Society of Believers in Christ's Second Appearing established their first community in New York in 1776 after several years of traveling throughout the Northeast in search of converts. Early worship involved ecstatic dance, which is why they came to be called the Shakers. Mother Ann Lee's group believed in pacifism, equality, and living a life of simplicity separated from mainstream society. The Shakers were not alone in their desire to create an ideal way of life. Many other experimental communities who questioned religious and social norms began to form as early as the late 1700s.

This exhibition was made possible through a generous loan from Benjamin Rose. Special thanks to Benjamin and Toby Rose for all of their assistance with the exhibition.

[inset images from top to bottom]

Shakers near Lebanon c. 1850s

Mount Lebanon, New York

Collection of Benjamin Rose, San Francisco, California

R2012.2701.062

Shaker girls working in the garden near the ministry shop and meeting house c.1915

Canterbury, New Hampshire

Courtesy of Canterbury Shaker Village, Canterbury, New Hampshire

R2012.2703.00

Brother Delmer Wilson in his shop in front of a bandsaw c. 1910

Sabbathday Lake, Maine

Courtesy of the United Society of Shakers, New Gloucester, Maine

R2012.2702.001

Canterbury sisters preparing to go apple picking October 1918

Canterbury, New Hampshire

Courtesy of Canterbury Shaker Village, Canterbury, New Hampshire

R2012.2703.001

Workroom in the Church Family sisters' shop 1931

Photograph by William F. Winter Jr.

Hancock, Massachusetts

Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, D. C.

HABS MASS,2-HANC,11-2

R2012.2704.001

Sister Bertha Mansfield at her loom c. 1870s–1880s

Canterbury, New Hampshire

Courtesy of Hancock Shaker Village, Pittsfield, Massachusetts

R2012.2705.008

©2013 by San Francisco Airport Commission. All rights reserved