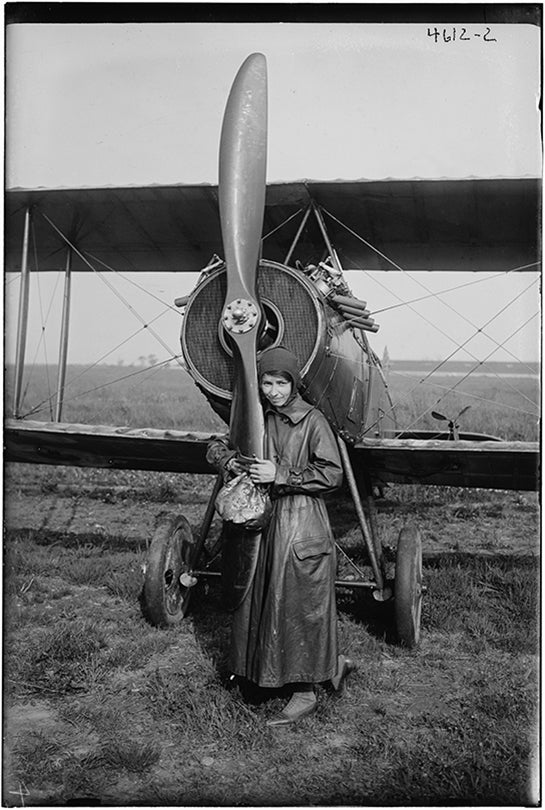

Katherine Stinson in San Francisco 1917

[above image]

Katherine Stinson wearing the medal she earned for her San Diego to San Francisco record flight, Tanforan Race Track, San Bruno, California December 30, 1917; photograph; Collection of the California State Library

As the large crowd scanned the horizon with anticipation for the awaited aerial superstar, the rumbling of the aircraft engine grew louder, and a small biplane was seen flying in from the north. The pilot gracefully circled and effortlessly alighted on the grass field, as the spectators let out a resounding applause. While displaying her charismatic smile, she shook hands with the numerous cameramen and received an official hero’s welcome from San Francisco Mayor James Rolph (1869–1934). Then the chicly-dressed aviator diligently inspected her complex airplane, the control surfaces, the support wires, and the V-8 Curtiss engine. The day was December 30th, 1917, and the world-famous aviator Katherine Stinson (1891-1977) was preparing for her first San Francisco public flying exhibition at San Bruno’s Tanforan Race Track.

[image]

Katherine Stinson inspects the OXX-6 V-8 engine of her Curtiss-Stinson JN-4/S-3 Special biplane at Tanforan Race Track, San Bruno, California December 30, 1917; photograph; Courtesy of San Diego Air & Space Museum

Katherine Stinson was one of only a small number of licensed women aviators performing worldwide at this time. In the 1910s, male aviators outnumbered women pilots (or “aviatrixes”) by over twenty to one. Yet Stinson proved that women could fly airplanes as well as men, if not better. Born in Fort Payne, Alabama, Stinson learned to fly to help pay for her music education. Initially, she could not find an instructor willing to train her, but ultimately, she persuaded Max Lillie (1881–1913) of the Wright School to give her lessons. In 1911, after just four hours of training, she was able to fly solo. In 1912, at the age of twenty-one, Stinson became only the fourth woman in the United States to obtain a pilot’s certification. Often referred to by the diminutive moniker “the Flying School Girl,” Stinson quickly became a star aerobatic performer at air meets and exhibitions. The first woman to perform an aerial loop, she performed the stunt hundreds of times without a single mishap. She was also the first woman aviator to perform flying exhibitions in China and Japan.

Several weeks before the Tanforan event, on December 11, Stinson piloted her aircraft nonstop from San Diego to San Francisco, covering a distance of 606 miles and setting a new endurance record. The biplane she flew was custom built by the famed aviator Glenn H. Curtiss (1878–1930). It combined the fuselage of a Curtiss S-3 triplane with a set of biplane wings and tail surfaces from a JN-4 Jenny and was powered by a liquid-cooled, one-hundred-horsepower Curtiss OXX-6 V-8 engine.

[image]

Katherine Stinson at the Curtiss Plant, Buffalo, New York June 19, 1917; photograph; Collection of the National Air & Space Museum, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.

She flew her open-cockpit biplane over Los Angeles, the Mojave Desert, the Tehachapi Mountains, California’s Central Valley, and finally on to San Francisco. To get over the Tehachapi Mountains she ascended to over seven thousand feet. Upon arriving to a grand military celebration at the Presidio, after over nine hours of flying, she said to a reporter, “I was very happy; I had done something that men held worthwhile. But happy as I was, I was also very tired and very hungry—and my lips were cracked by the cold headwinds that I battled all the way up from San Diego.”

[image]

Katherine Stinson in front of her Curtiss-Stinson JN-4/S-3 Special biplane 1917; photograph; Collection of the Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.

Stinson returned to San Francisco on December 28th. The next morning, she caused downtown ferry attendants and hurried commuters to stop in their tracks and gape when she jumped into one of aviator Art Smith’s (1890-1926) powerful baby race cars and skidded around the wet and slippery streets of San Francisco. It was a planned stunt to promote her upcoming aerial performance and the motorcar races scheduled to follow. A large portion of the proceeds from the day’s events would go to support the Grizzlies, a San Francisco-based California National Guard artillery regiment preparing for World War I in Europe.

The next day, Stinson’s stirring performance at Tanforan included her signature looping the loop stunt, flying upside down, and the dancing of an aerial tango. It also featured her ascending to three thousand feet, plummeting like a hawk, and then slowly gliding just over the heads of the crowd. Upon landing, she addressed the excited spectators, “Thank heaven we’re all here.” After she completed the aerobatic performance, she again bounded into one of Art Smith’s baby racers and sped around the track with the other race drivers. During the event, she was also given a medal in honor of her record flight from San Diego to San Francisco. The San Francisco Chronicle described her flying performance that day as nothing less than “thrilling.”

Following the San Francisco event, Stinson traveled to Sacramento for a New Year’s Day aerial exhibition, also to support the Grizzlies. She also petitioned to fly for the military during this time but was denied due to her gender. Instead, she later joined the ambulance service for the Red Cross in Europe, where she contracted tuberculosis. After the war, she quit flying, and to help in the treatment of her disease, moved to New Mexico, where she became a successful architect.

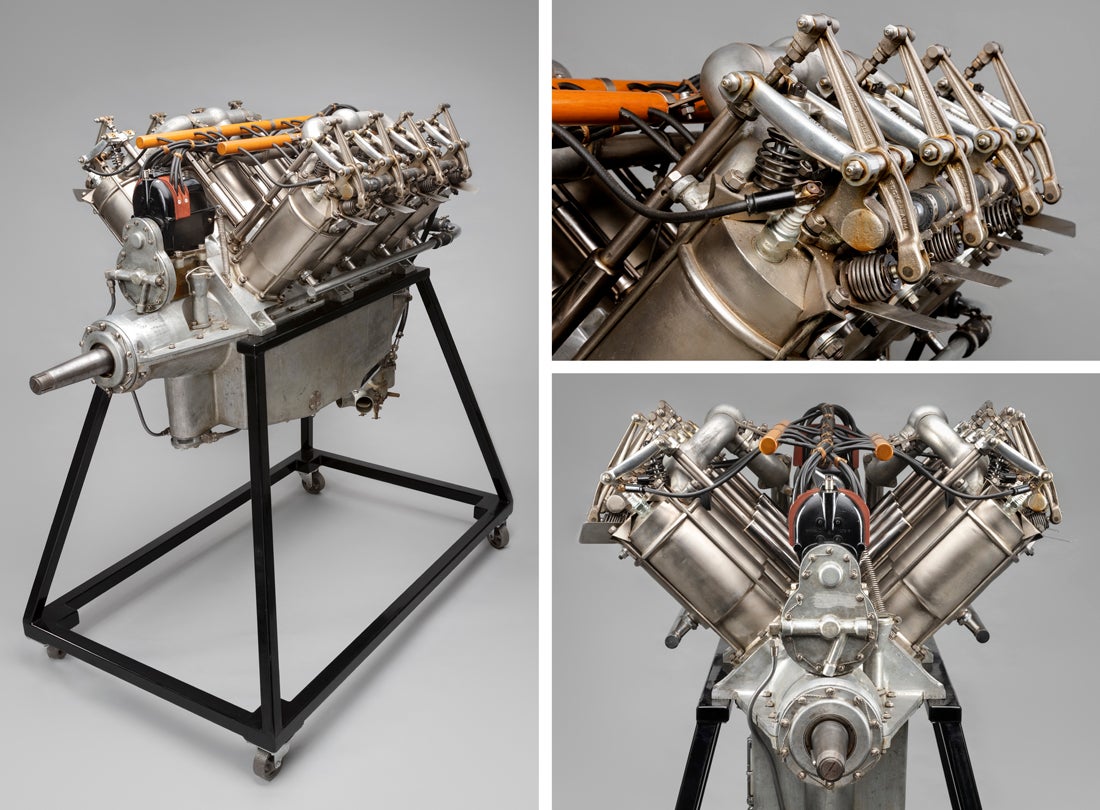

An original Curtiss OXX-6 V-8 aircraft engine, like the one installed in Katherine Stinson’s Curtiss biplane, is presented in the SFO Museum aviation exhibition Going the Distance: Endurance Aircraft Engines and Propellers of the 1910s and 20s. The exhibition also includes video excepts of movie footage taken during Stinson’s Tanforan performance.

[images]

Curtiss OXX-6 V-8 aircraft engine c. 1917; aluminum, steel, rubber; Courtesy of the Frederick W. Patterson III Collection

View the complete video of Stinson’s exhibition at Tanforan: internet-archive.org/details/KayStinson1917

See the online exhibition: www.sfomuseum.org/exhibitions/going-the-distance

Dennis Sharp

Curator of Aviation

SFO Museum